The concepts of our world are stuck in an ever-evolving cycle of definition and context alterations. If you were to ask individuals from different generations the meaning of a specific chance, odds are you may receive vastly different answers depending on who you ask. The saying goes that it is the same as it ever was, but in this situation, it seems the only thing remaining the same is the consistency of change.

With the way things constantly shift and change in our world, it’s no surprise that writing would fall victim as well. In Lisa Dush’s article “When Writing Becomes Content,” this concept of change in the world of writing is discussed.

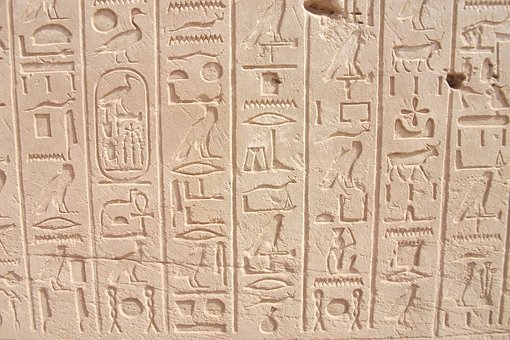

Writing has existed essentially as long as we have. Throughout all of history, we have evidence and artifacts of our predecessors’ writings, and yet today, writing is viewed differently than in years passed. As the title states, writing has taken on the form of strictly “content” as opposed to a form of communication, story-telling, and even preserving history. With the recent push of digital content, or digital writing in this scenario, the meaning and definition of artforms has been altered in a way that’s diminishing the world and value of the creators and their creations.

Dush defines content as being “conditional, computable, networked, and commodified. New vocabulary benefits a field if it illuminates phenomena that current terms ignore or obscure” (174). Essentially, Dush is saying here that content is looked at based on how well it is received, and not necessarily the information that it gives. Writing is oftentimes looked at in the same light, being viewed for how well it can benefit a network or how much attention it receives rather than what is being said through the writing.

Within her article, Dush quotes Pullman and Gu on how writing as we’ve known it is being transformed in a way that views the craft as a means of content:

No longer can writers think in terms of text or even publications. They have to start thinking of asset management: the strict separation of form and content to allow for seamless repurposing of content, data mining, reduplication of effort control mechanisms, and writing in a collaborative environment with multiple authors and multiple purposes feeding off of and contributing to a conglomeration of assets that collectively make up a content archive.”

Dush explains that writing is no longer “characterized […] by being finished or published” (176) and is instead looked at for how it can be adaptable, changed, or altered to fit a certain standard for those who wish to use it. It’s no longer looked at for the skill that such a craft requires, and is instead a means to easy profit. However, just because the modern use of writing is different from its historical use is not in and of itself a negative thing. As everything else in our society, writing must adapt to meet the standards that it’s needed for in our day and age, but its status as digital data should not be the only viewpoint. Writing should not be something that is only “assembled and within and pushed out to networks” (178). Writing is an artform, and like every artform, there is a degree of skill, thought, and care that goes into a piece. While writing can indeed be digital content, it is so much more than that.

Overall, Dush has given a very clear stance on the modern view of writing and how this shift in viewpoints can potentially alter the future of the profession in a negative way, more so than it already has. Writing has evolved to be marketing and network advancements, while the personal side of the writer is being ignored or disregarded. While writing of course can and should be used in this manner, it is important that it does not become its only standard.

Dush, L. (2015, December). When Writing Becomes Content. NCTE. Retrieved from https://library.ncte.org/journals/CCC/issues/v67-2/27641.

Pullman, George, and Baotong Gu. “Guest Editors’ Introduction: Rationalizing and Rhetoricizing Content Management.” Technical Communication Quarterly17.1 (2008): 1–9. Print.